Often, the most challenging part of giving a lesson is getting the children excited and ready to learn. Here are seven strategies to ensure your presentation gets off to a good start.

1. Check your attitude: You need to believe in the value of what you’re going to present. The children will smell your fear or hesitation a mile away. If a particular topic scares you, spend more time with it. Read, listen to podcasts, watch videos, use your hands to explore the concept, and find new ways of looking at the subject. When you love it, your students will likely love it. If you’re worried your lesson will be boring, practice ahead of time. A trainer once told me that during the first year you teach in a classroom, you need to practice every single lesson ahead of time.

2, Prime the pump: Sometimes, I’ll start a conversation about the topic a while before the lesson (like at breakfast or in the car). And that way, when it’s time for the lesson, I can say: “Remember when we talked about how angles can be found in buildings, trees, baseball fields and playgrounds? Well, did you know that some of those angles you saw have names, just like you have a name? Look over here…”

3. Play to their sensitivities: Second-plane children have a sensitivity for imagination. For the first time in their lives, they can craft in their minds wondrous images that they’ve never seen or experienced before. They also have a sensitivity for knowledge and culture; they want to know the why and how of everything. Use that to your advantage by starting your lesson with: “Have you ever wondered…” or “Have you ever noticed…”

4. Tell stories: “We’re wired for story”, writes Brene Brown. And it’s true. I recently told my seven-year-old son a funny story about dealing with a pushy bike salesman; he asked me to re-tell it five times in a row and laughed heartily each time.

“Travel stories teach geography; insect stories lead the child into natural science; and so on.”

– Dr. Maria Montessori

Tell lots of stories! In the car and during meals, get used to telling funny, interesting, and moving stories about your own life. Do this to hone your craft, but also because when you introduce a lesson by saying, “I have a story to tell you”, they’ll be more inclined to listen.

For story-telling inspiration, listen to this podcast episode where master storyteller Jay O’Callahan shares his strategies for crafting a good story (and tells a wondrous story of his own along the way). For stories that tie into the Montessori elementary curriculum, read “The Deep Well of Time” by Michael Dorer.

5. Entice them with interesting follow-up work: Sometimes it’s great to let children choose how and when they’re going to follow up on what you’ve presented, but other times, dangling an enticing follow-up activity will draw them to the lesson. Don’t divulge too much information; offer just enough detail to draw them in. You could say, “How would you like to draw all over the kitchen floor? When we’re done learning about different types of angles, you get to do just that!” Suddenly eyes are wide open, faces are turned towards you, and the children are ready to learn. If they ask you questions about the mysterious follow-up, you can just lightly say, “Ahhh, you’ll find out soon enough!” This approach works particularly well for lessons that are more dry and straightforward.

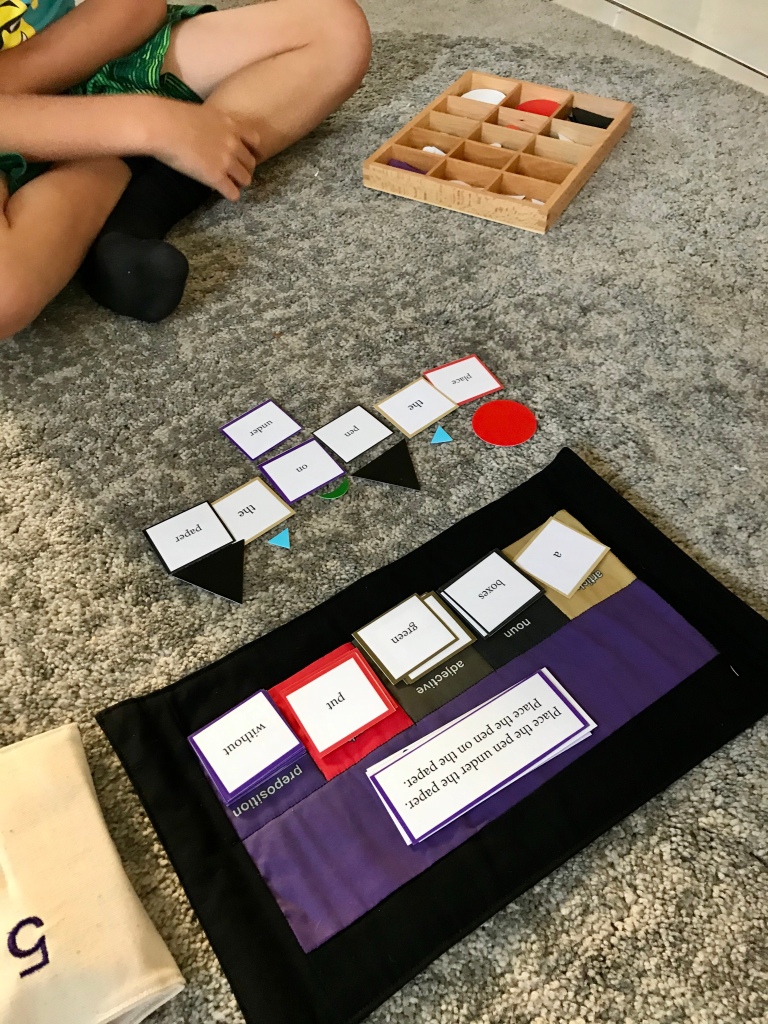

6. Ask for helpers: To get and keep children engaged, let them get their hands on the materials as soon as possible. Give them jobs ahead of time so their presence at the lesson has some significance to them. “Today I want to show you something the Ancient Egyptians discovered five thousand years ago, that we still use in our lives today. Zach, can you be in charge of the push pins? Bill, can you be the stick selector? Olivia, can you be the label reader?”

7. Be ready: In my trainings, I was told that you prepare all the materials with the children prior to the lesson so they know where everything is and what they need. However, I’ve found that in my homeschooling environment, it helps to bring out the materials ahead of time, feature them attractively, and direct the children’s attention towards the rug or table when they seem to be at a good stopping point in their other work. This works particularly well for my seven-year-old son and his elementary-aged friends who visit us to use our materials (I still follow the more traditional approach with my Primary-aged daughter).

Now, go forth and, as Dr. Montessori used to say, “seduce the child”!

*This post includes affiliate links.

Enjoy? Then please share!

Then we tried making bubbles holding our fingers in an OK sign, which led to catching bubbles (this is much easier if your hand is covered in bubble solution). That led to talking about surface tension and surfactants, which led to observing the bubbles we were holding in our hands.

Then we tried making bubbles holding our fingers in an OK sign, which led to catching bubbles (this is much easier if your hand is covered in bubble solution). That led to talking about surface tension and surfactants, which led to observing the bubbles we were holding in our hands.