A few weeks into his first-grade year, my formerly sweet and relatively cooperative son began acting sassy, cocky, and entitled. Requests for help were met with groans and eye-rolls. Limits were countered with sighs and “whatever“s.

We gave him the benefit of a doubt: Surely he was just imitating his older classmates’ rude behaviors. Or maybe this was a misguided attempt at being more independent. All my friends’ children were acting the same way, so it was probably a developmental phase. Regardless of the reason, I dealt with entitled children all day long at work and I wasn’t about to put up with the same behaviors from my son at home.

My husband and I gave Zachary a speech about behavioral expectations in our family. He gave us a sigh and an eye-roll. This was going to be harder than I thought…

A quick Google search on books about childhood entitlement led me to “The ‘Me, Me, Me’ Epidemic: A Step-By-Step Guide to Raising Capable, Grateful Children in an Over-Entitled World”. I was pleasantly surprised to find that the book revolves around the principles of Positive Discipline, which I’ve used for years.

The first practical suggestion for countering entitlement is called “Mind, Body, and Soul Time” (MBST). It requires each parent to set aside just ten minutes a day to “be fully present in mind, body, and soul and do whatever your child loves to do.”

Ten minutes a day sounded like a paltry amount of time until I started seeing the day from my son’s perspective. From wake-up to bedtime, I was always busy with something – too busy to spend ten minutes one-on-one with him.

When he woke up, I was making breakfasts, packing lunch boxes, and getting everyone out the door on time. Even though Zachary and I spent the day together at school, we were always surrounded by other children and adults. Then at 5pm it was a mad rush to pick up his sister, drive home, get dinner made in 15 minutes, and sit down for ten minutes to eat as a family. My husband would read the kids a book and tuck them in while I cleaned the kitchen, answered work emails, and planned the following day’s lessons. Our life ran on a strict timetable and as hard as I tried, I couldn’t find ten minutes to just be with him without sacrificing some essential task and sending the whole house of cards crashing down.

Three months after reading the book, we decided as a family to walk away from the madness of our lifestyle. We shifted into the slow pace of unstructured homeschooling and discovered something we never had before: TIME.

Without the need to wake up at 6am, my son could go to bed later. And without the need to hurriedly clean the kitchen and answer work emails, I could spend time with him. And so, I started reading to him for an hour each night (his favorite thing to do).

Within a week, my husband pointed out, “Zachary is so much happier.” It was true: my little boy began to laugh again. Then, we noticed another change. He became physically affectionate. The child who had been pulling away from us began moving back into our lives. He started folding his 4’4″, 70 lb. frame into our laps, requesting snuggles. Or he’d jump into our arms and wrap his arms and legs around us in a full-body hug.

And then, about a month in, we noticed it. The entitlement, sass, and attitude had disappeared almost completely. Requests for help were now met with an agreeable attitude; limits were either accepted or discussed rationally. We even started hearing a phrase we’d never heard from him before: “How can I help?”

Sure, he has his moments, especially when he’s hungry or tired. But overall, he’s a different child.

He’s a different child because I’m a different mother and we lead a different lifestyle.

Now, I’m certainly not saying that everyone should drop what they’re doing and homeschool. But we need to stop justifying rudeness and entitlement as “normal” parts of growing up. These behaviors are cries for help from little beings who are evolutionarily primed to connect. So please, find those ten minutes, before it’s too late.

“The impulse to be good arises less from a child’s character than from the nature of a child’s relationships. If a child is ‘bad’, it’s the relationship we need to correct, not the child.” – Gordon Neufeld, “Hold On to Your Kids”

***

This post contains affiliate links that allow me to continue providing the quality content you enjoy at no cost to you. Thank you!

Enjoy? Then please share!

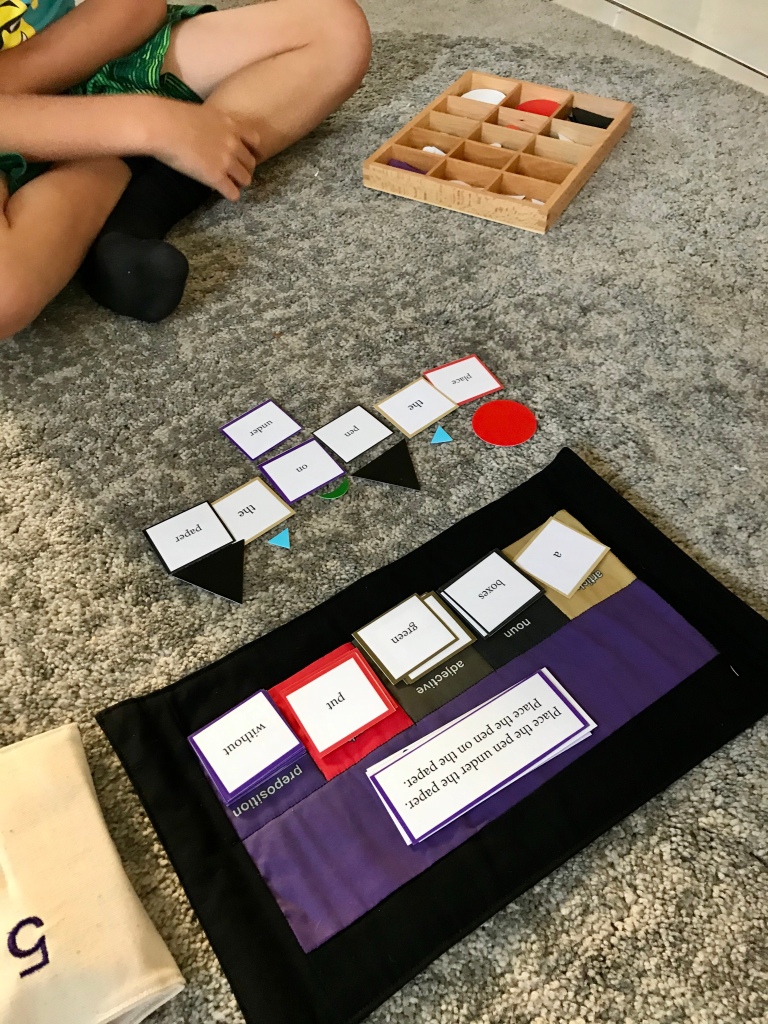

They’re great for a homeschool environment because they don’t take up any shelf space. Their initial purpose is to help the child first

They’re great for a homeschool environment because they don’t take up any shelf space. Their initial purpose is to help the child first  Find the number: Ask the child to set out the hundred chain with the corresponding arrows, while you cut up a few blank paper arrows (cut little rectangles and trim the corners to make arrows). Write a number on the arrow (any number between 1 and 99) and have the child place the arrow on the corresponding bead. If you notice mistakes, you can either let it be for now (and encourage more practice) or invite the child to count from the nearest tens-arrow (e.g. if the paper arrow says “26” and it’s in the wrong spot, invite the child to count linearly from the “20” arrow).

Find the number: Ask the child to set out the hundred chain with the corresponding arrows, while you cut up a few blank paper arrows (cut little rectangles and trim the corners to make arrows). Write a number on the arrow (any number between 1 and 99) and have the child place the arrow on the corresponding bead. If you notice mistakes, you can either let it be for now (and encourage more practice) or invite the child to count from the nearest tens-arrow (e.g. if the paper arrow says “26” and it’s in the wrong spot, invite the child to count linearly from the “20” arrow). can present a new challenge by having them find the missing number in a number sequence. The first few times you do this, you can use the regular arrows for any chain and hide one behind your back. Ask the child to lay out the arrows and tell you which one is missing. (e.g. The child lays out 5, 10, 20, 25 and tells you that 15 is missing.)

can present a new challenge by having them find the missing number in a number sequence. The first few times you do this, you can use the regular arrows for any chain and hide one behind your back. Ask the child to lay out the arrows and tell you which one is missing. (e.g. The child lays out 5, 10, 20, 25 and tells you that 15 is missing.)

Polygons: The chains provide a fun exploration of shapes, from triangle to decagon. Have the child carry all the chains on a tray to a large rug and ask her to make a closed shape with each chain imagining that the center was pressing out evenly on all sides. Then ask her how many sides each shape has. If you have a Geometry Cabinet, ask her to find the corresponding shape from the cabinet and put it inside or next to the bead shapes. The child can write on a slip of paper the number of sides each shape has, and then you can give the names. You can do a three-period lesson with a Primary child, and you can make an etymology chart with an Elementary child. The child can also build the shapes around each other, with the square surrounding the triangle, the pentagon surrounding the square, etc.

Polygons: The chains provide a fun exploration of shapes, from triangle to decagon. Have the child carry all the chains on a tray to a large rug and ask her to make a closed shape with each chain imagining that the center was pressing out evenly on all sides. Then ask her how many sides each shape has. If you have a Geometry Cabinet, ask her to find the corresponding shape from the cabinet and put it inside or next to the bead shapes. The child can write on a slip of paper the number of sides each shape has, and then you can give the names. You can do a three-period lesson with a Primary child, and you can make an etymology chart with an Elementary child. The child can also build the shapes around each other, with the square surrounding the triangle, the pentagon surrounding the square, etc. Then we tried making bubbles holding our fingers in an OK sign, which led to catching bubbles (this is much easier if your hand is covered in bubble solution). That led to talking about surface tension and surfactants, which led to observing the bubbles we were holding in our hands.

Then we tried making bubbles holding our fingers in an OK sign, which led to catching bubbles (this is much easier if your hand is covered in bubble solution). That led to talking about surface tension and surfactants, which led to observing the bubbles we were holding in our hands.